January 11th, 2022

Simple rules to avoid some range for loop pitfalls

Go “range” statement memory efficiency and its implications.

Memory efficiency is something worth aiming for. In the “pay what you use era” it can be a critical factor in the bill.

With that in mind, the engineers behind Go’s development designed a simple, yet efficient, way to iterate over arrays, slices, maps, strings and channels. Each data structure has its own implementation and the iteration over its values is slightly different.

- Maps have a randomized access, you should not rely on its order.

- Strings actually iterate over unicode points, sometimes this means multiple bytes.

- Slices and arrays are the simplest, iteration over the values preserving their order.

- Ranging over channel values blocks inside the loop until the channel is closed.

But how this relates with memory efficiency?

Well, think about it, where these values that you are accessing are being stored?

Dissecting range for loop

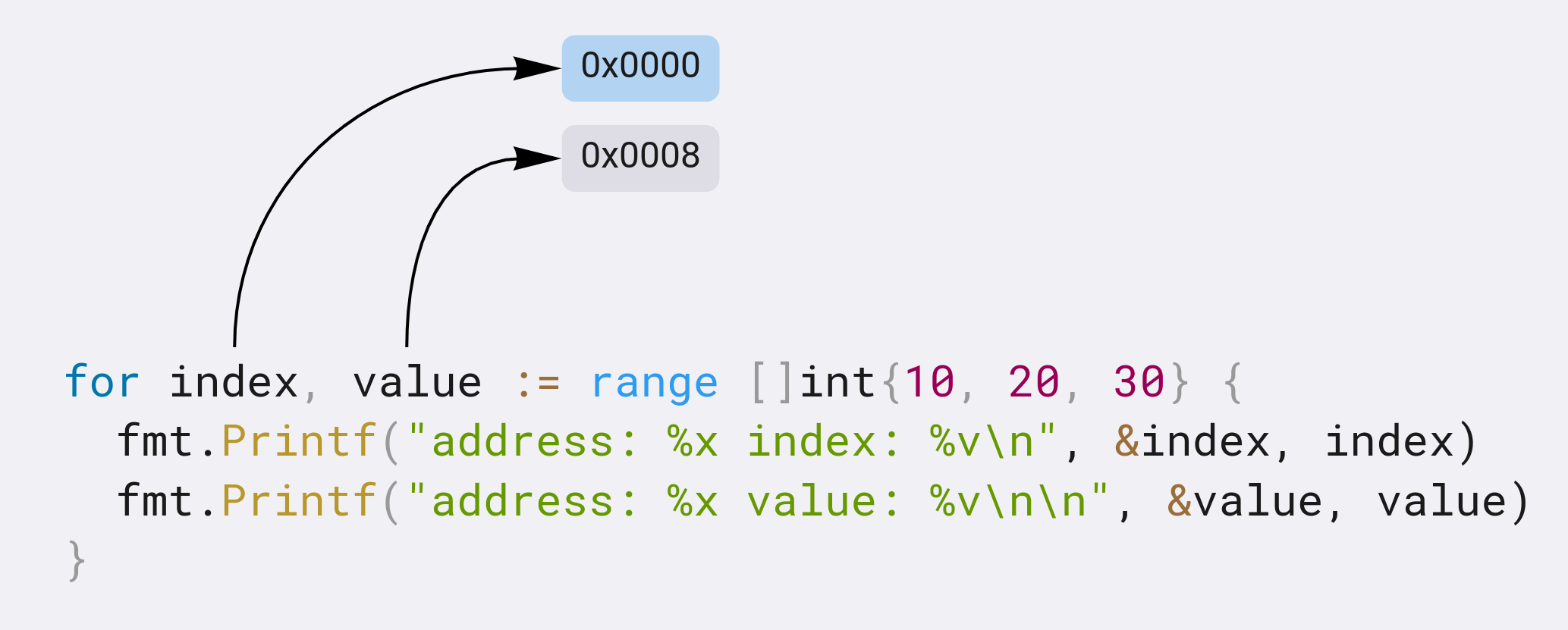

The range for loop iterates over the underlying data structure mutating the values of the iteration variables. This means that all the loop iterations values share the same memory location and this behavior, although being a good and efficient design, can end up causing misuse.

//main.go

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for index, value := range []int{10, 20, 30} {

fmt.Printf("address: %x | index: %v\n", &index, index)

fmt.Printf("address: %x | value: %v\n", &value, value)

}

}

// Output:

// address: c000018030 | index: 0

// address: c000018038 | value: 10

// address: c000018030 | index: 1

// address: c000018038 | value: 20

// address: c000018030 | index: 2

// address: c000018038 | value: 30

In a simple loop, where your process is contained inside the loop scope, this implementation detail is not relevant. When you need this values outside the loop scope is where the knowledge of these implementation details are valuable.

Range and closures

Closures are a way of injecting state into a function. This is achieved by sharing the outer scope variable reference with the inner function scope (you can read more about them here).

Applying to our range for loops case, the memory location of the variables inside the function scope are actually the same used by the loop to iterate over the values. If the function is not executed inside the same iteration it is defined, by the time it executes the value of the variables it received through closure will not be the same as when it was defined.

//main.go

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var functions []func()

for index, value := range []int{10, 20, 30} {

functions = append(functions, func(){ fmt.Printf("index: %v, value: %v\n", index, value) })

}

for _, f := range functions {

f()

}

}

// Output:

// index: 2, value: 30

// index: 2, value: 30

// index: 2, value: 30

Maybe you expected the output to be the correct sequence through indexes 0 to 2, but remember closure is passing values through reference. When the functions are executed the iterations is complete, but since the range variables where referenced by the functions they are still available and have the last iteration value on them, and this is why all of them had the same values in the end. The code above works the same as the following, which uses pointers to pass the reference to the inner function.

//main.go

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var functions []func()

for index, value := range []int{10, 20, 30} {

f := func(index, value *int) func() {

return func () {

fmt.Printf("index: %v, value: %v\n", *index, *value)

}

}

functions = append(functions, f(&index, &value))

}

for _, f := range functions {

f()

}

}

// Output:

// index: 2, value: 30

// index: 2, value: 30

// index: 2, value: 30

The same behavior can happen when the variables are passed by reference to a go routine started inside the loop (for example, in a fanout pattern), since they will probably outlive the loop iteration scope, and have access to the variables after the iteration is done.

If you want to have access to each iteration value inside a scope that outlives the loop, there are two simple techniques you can use: declare a new variable inside the loop (forcing it to use a different memory location to each iteration) or, even simpler, pass the arguments by value.

//main.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var functions []func()

for index, value := range []int{10, 20, 30} {

// Declaring new variables to receive the index and value.

i, v := index, value

functions = append(functions, func(){ fmt.Printf("index: %v, value: %v\n", i, v) })

}

for _, f := range functions {

f()

}

fmt.Println()

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for index, value := range []int{10, 20, 30} {

wg.Add(1)

// Receiving the arguments by value.

go func(i, v int) {

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Printf("routine: index: %v, value: %v\n", i, v)

}(index, value)

}

wg.Wait()

}

// Output:

// index: 0, value: 10

// index: 1, value: 20

// index: 2, value: 30

//

// routine: index: 2, value: 30 |

// routine: index: 1, value: 20 |- These can be shuffled

// routine: index: 0, value: 10 | since they are concurrent.

These pitfalls are usually amplified when concurrent processes are being developed, since they are harder to track. They are not exclusive of closures and need to be observed every time you pass things by reference in a range for loop.

I face this kind of language details as tool knowledge and as “code artisans” we should know well our tools and techniques. Every engineering decision comes with its price and Go has its share of opinionated decisions, make sure you know their implications when you use it.

By understanding the details behind the language tools we can make good decisions and avoid misusing them.